"Science is a lot like a circus. You're constantly amazed by what nature can do," says Fulbright Scholar from UHK, Dr. Marie Drábková

Life is Full of Surprises – whether you're out in the field, in the lab, or performing aerial acrobatics. Dr. Marie Drábková from the Faculty of Science UHK, currently working at the University of California Santa Barbara thanks to a Fulbright scholarship, explores the evolution of parasites and shares her international experiences with students. On the occasion of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, celebrated today, February 11, we bring you a glimpse into the inspiring career of this scientist.

Fieldwork vs. Laboratory

Dr. Marie Drábková, now based at the Faculty of Science at the University of Hradec Králové (UHK), developed her interest in biology during her studies at the University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice. One of the first topics we discussed was fieldwork in science, even though Dr. Drábková currently spends most of her working day analyzing data in the lab. A key moment in her professional development was completing several field courses in marine biology, which she considers "a great opportunity to engage with organisms that students often only see in textbooks."

The courses took place in coastal areas, such as Egypt and Croatia. Marie Drábková describes them as a combination of field research and practical learning: "Essentially, you take a group of students to the sea, where they have the chance to study ecosystems directly in their natural environment. What they know from textbooks – like marine invertebrates, of which there are many – they can literally get their hands on."

Fieldwork is a great opportunity to engage with organisms that students often only see in textbooks.

Field research, which remains a part of her work today (albeit more marginally), involved collecting and processing samples afterward. "Along with the teaching, we always collected a lot of material for analysis. I see it as a big advantage because even after returning home, we could continue working on these samples, analyzing them, and discovering new connections," explains Dr. Drábková. During the COVID-19 restrictions, when international excursions were limited, the research could continue thanks to these previously gathered materials – mainly due to collaboration with colleagues abroad.

Although Marie Drábková currently focuses mainly on researching crustaceans that parasitize vertebrates (not exclusively marine), her experiences in marine biology fieldwork remain a solid part of her expertise. She says, "The world's oceans are vast and not all that far away. I think it's important that students here also have the chance to learn about them."

From Dicyemids to Tongue Worms

In her dissertation, Drábková studied Mesozoa, tiny marine parasites. Using advanced DNA analysis and population genetics methods, she clarified their placement in the broader animal family tree and uncovered how dicyemid parasites live and spread in their cephalopod hosts, primarily in the kidneys of octopuses and cuttlefish. "That's why they're sometimes called 'sépiovky' in Czech, but that term isn't used much." Her fascination lies in placing the life stories of these small creatures within broader evolutionary contexts.

Dicyemids are often considered parasites, although their impact on their hosts isn't clearly harmful. "In some octopus species, dicyemids seem to be more like symbionts than pests," Dr. Drábková explains. Studying these organisms provides important insights into their evolution and possible mutualistic relationships with hosts, opening doors for further exploration of complex interactions in marine ecosystems and beyond.

Ethics plays a key role in contemporary biology, even in the study of invertebrates. "Although the rules for working with invertebrates aren't as strict as with vertebrates, there are exceptions," Marie Drábková notes. Cephalopods, like octopuses, were recently classified under the same protection category as vertebrates. "This means that any experiment requires a permit, justification for the number of individuals used, and assurance that they are handled ethically," she explains. Marie Drábková herself doesn't use experimental methods; in the past, she analyzed octopuses based solely on samples purchased from fishermen. She considers ethical standards crucial for maintaining the credibility of science and respect for living organisms.

This perspective likely reflects the influence of her personal inspirations for studying nature – naturalists like David Attenborough and Jacques-Yves Cousteau – even if her final dissertation path was a little less adventurous. "I just asked around the department if anyone had an interesting topic. Coincidentally, someone did, so we met over coffee and got the ball rolling."

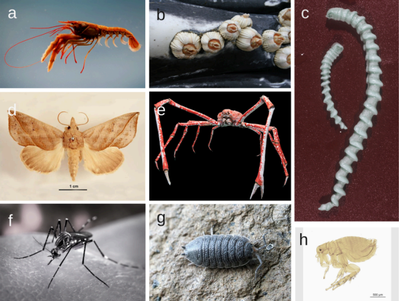

Her previous research now continues in the study of other parasites, Pentastomida, commonly known as tongue worms, in the U.S. At the Department of Life Sciences (Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology) at the University of California, Santa Barbara, she conducted a Fulbright-funded project titled "Evolution and Origin of Tongue Worms (Pentastomida), Enigmatic Parasites of Vertebrates." Tongue worms live as parasites in the respiratory tracts of vertebrates. "Our goal is to find out from which group these parasites evolved and exactly where they belong in the evolutionary tree of life," Dr. Drábková explains. Although these parasites are crustaceans (shellfish), they resemble white worms, highlighting their dramatic lifestyle changes during evolution.

Our goal is to find out from which group parasites Pentastomida evolved and exactly where they belong in the evolutionary tree of life.

The research uses advanced genomic methods, allowing for comparisons between the genetic material of tongue worms and other crustaceans, methods Marie Drábková previously used in her dissertation. "We're focusing on phylogenetics – constructing family trees of species and groups of organisms based on genetic data. This approach allows us to better understand the evolutionary history and adaptations of these parasites," she adds.

An interesting aspect of her work is the use of microsatellites, short repeating sequences of DNA that vary between individuals and species. "With these genetic markers, we can determine how closely related individuals are and better understand their evolution and life strategies. For instance, we can investigate whether parasitic infections occur once or repeatedly," she explains.

When asked if it was difficult to obtain a Fulbright scholarship, Dr. Drábková responds matter-of-factly: "To be honest, I just wanted to give it a shot. Either it would work out, or it wouldn't. The Fulbright committee probably liked my project, for which I'm grateful. I also want to thank my colleagues who wrote recommendation letters. I didn't get to read them, but they must have been very positive since things turned out well. Otherwise, the application process isn't too complicated – if you're up for the challenge, it's worth it. California is a beautiful place."

During her current stay in the U.S., Marie Drábková is fully dedicated to her research. Her typical workday starts early morning when she checks important emails and plans the day ahead. "Most of my time is spent at the computer, working on data analysis and optimizing scripts," she describes. The analyses run on powerful servers and cover a broad range of tasks, from data organization to interpretation.

During her current stay in the U.S., Marie Drábková is fully dedicated to her research. Her typical workday starts early morning when she checks important emails and plans the day ahead. "Most of my time is spent at the computer, working on data analysis and optimizing scripts," she describes. The analyses run on powerful servers and cover a broad range of tasks, from data organization to interpretation.

The project also requires regular communication with colleagues in person and via virtual meetings. "We have weekly team meetings where we discuss progress and plan the next steps," she adds. Even though lab research might seem monotonous, Dr. Drábková enjoys the moments when she uncovers new connections or results that can push the research forward, even if only by a small step.

Research Life and Balancing Work with Family

Despite the demanding lab work, Marie Drábková occasionally finds time to return to the field. Recently, she participated in a project in the Giant Mountains, where she and a student conducted research on peat bogs. "It was a great experience that provided us with valuable data for further research," says Dr. Drábková. Fieldwork doesn't always require direct participation – she has often collaborated with colleagues worldwide who sent her samples. This is one of the great advantages of globalized, internationalized science.

Field biology also intertwines with family life. Besides being a successful scientist, Marie Drábková is a caring mother of lively twins. "We combined our sample collection in the Giant Mountains with a family vacation," she says with a smile. "The kids were thrilled, always collecting something in test tubes and asking me if there was 'something inside.'"

For her Fulbright stay in America, Marie Drábková brought her whole family, which she considers a given. "My husband takes care of the kids, who go to kindergarten twice a week to socialize with peers," she explains. But most of the time, they spend together as a family. They enjoyed going to the beach, where the kids collect shells, or at playgrounds and bike trails. "Building Lego is a big hit at our house right now," she adds with a smile. On weekends, they make the most of the natural surroundings. "Santa Barbara is a great place for family life. On weekends, we go on trips to the mountains or camping – the nature here is stunning," she says.

Relaxation is an integral part of Marie Drábková's life. Besides family activities, she is also involved in modern circus arts, specifically aerial silk acrobatics. "It's something that really energizes me and allows me to switch off from scientific work," she explains. Drábková even teaches beginner courses, sharing her passion for this perhaps slightly unusual discipline. "In many ways, science is like a circus. You're constantly amazed by what nature can do. And then comes our role – gradually explain these wonders," Dr. Drábková concludes with an amused look.

Her Work at UHK

One key difference between Marie Drábková's work in the U.S. and at the University of Hradec Králové is the research group environment. "In Santa Barbara, I'm part of a lab where colleagues work on similar topics, so we often discuss our work. I think it benefits all of us," she explains. She appreciates the greater independence in the Czech Republic, where she is still building her research group.

Marie Drábková is happy to return to the Czech Republic from the U.S., even though she enjoys her work overseas. "I'm going back, and I'm looking forward to it. Hradec is my home base. Plus, it's a condition of the Fulbright scholarship that you return for two years to pass on what you've learned," she replies.

I'm going back from the USA, and I'm looking forward to it. Hradec is my home base.

Her path to Hradec Králové led through the University of South Bohemia and maternity leave, after which she decided to return to science. "It was all just a coincidence, like many things in life. I'm originally from Chrudim, so Hradec is nearby. I was on maternity leave in Chrudim because I still have family there who helped me and still do. Then I asked if there was an opportunity for scientific work at UHK, and it turned out there was. I've been working here ever since, and I'm more than satisfied," she explains.

Regarding the future, Marie Drábková doesn't have a specific academic destination in mind. "I don't have a dream institution – I just want to continue doing what I love, develop my research, and share experiences with students." At UHK, Dr. Drábková teaches bioinformatics, among other subjects, and looks forward to showing students what she's learned in the States. "It's challenging for students at first – most analytical tools in bioinformatics and data servers run on Linux systems. That means no graphical interface, and you work more with command lines. But once they master these basic skills, they usually do great. I'm really looking forward to continue working with them," concludes Dr. Marie Drábková.

Mgr. Marie Drábková, Ph.D.

Mgr. Marie Drábková, Ph.D.

Marie Drábková completed her bachelor's, master's, and doctoral studies at the University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice, where she earned her PhD in biology in 2022. Her research focuses on phylogenomics and parasitology, specializing in the study of parasite evolution.

Dr. Drábková works as an assistant professor at the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Hradec Králové. Since 2023, she has been teaching bioinformatics and biology there. Previously, she worked as a biologist at the Institute of Parasitology of the Czech Academy of Sciences in České Budějovice (2014-2019) and as a teaching assistant in molecular ecology and a field course in marine biology at the University of South Bohemia.

For her outstanding research, presented in her dissertation, she received the Dean's Award in 2022.

Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Hradec Králové